Contents

Turbochargers have been around since the early 1900s, when they were developed for airplanes, much like superchargers were. They didn’t find their way onto car engines until the 1960s with the Oldsmobile JetFire, which only lasted for two model years. The first OEM production twin-turbo gas engine didn’t come along until the 1981 Maserati Biturbo.

Twin-turbos allow smaller engines to produce horsepower and torque equal to that of larger, less efficient engines—yielding better fuel economy, lower emissions, and in many cases, more consistent performance.

What Is a Twin Turbo?

As we described a few years ago, a turbocharger is a form of supercharger. It uses exhaust gasses to spin an impeller that draws fresh air into the compressor housing, compresses the air, and then sends it to the engine. Turbos have replaced many belt-drive superchargers (also known as blowers) in the high-performance world because turbo power is free power—there is little to no parasitic horsepower loss.

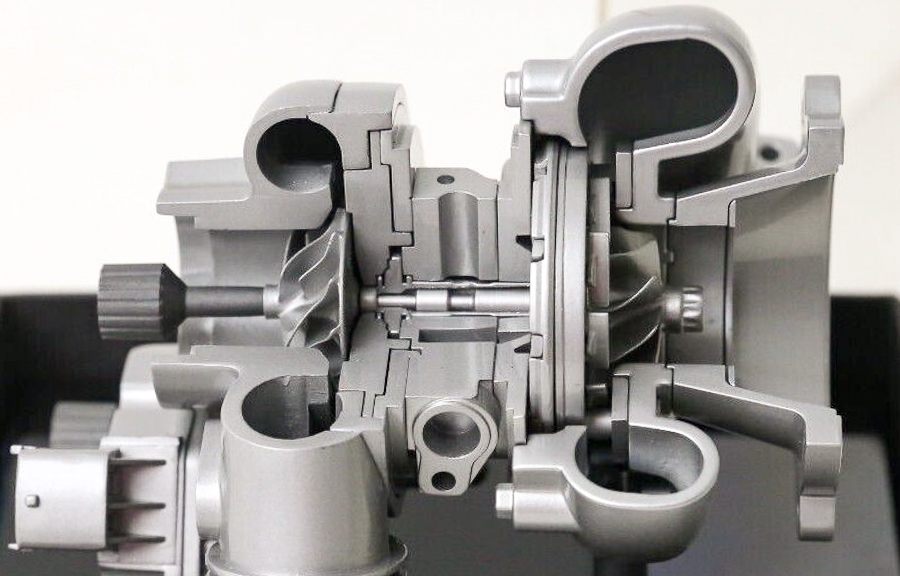

The exhaust-driven turbine (left) transfers otherwise wasted energy through a shaft to the compressor impeller (right).

A belt-driven supercharger, in contrast, causes engine drag due to the increased effort on the engine to spin the rotors. The faster it spins, the more drag is generated from friction, even with oiled bearings. The average loss from a belt-driven blower ranges from 5 to 15 percent, which is negated by the much higher performance gains.

Turbochargers and, more importantly, twin-turbos have allowed manufacturers to get huge power output from relatively small engines.

Shop now for car & truck turbos

A turbocharged Nissan 3.0-liter V-6 engine

Twin-turbos are just what they sound like: two separate turbochargers mounted to an engine’s exhaust and plumbed to the air induction.

They reduce what’s known as turbo lag, a moment between hitting the throttle and the turbo spinning to reach the minimum rpm to generate boost. Single-turbo cars can have significant lag time because they use a larger turbo. A twin system can use two smaller, more efficient housings that spin up faster, reducing lag while also generating more consistent boost.

Types of Twin Turbos

While designs vary radically, several common types yield different levels of performance and efficiency.

Parallel Turbochargers

A Calloway parallel twin-turbocharged Corvette V-8 engine

The most common style is the basic parallel system, where same-size turbos are mounted to the engine, usually one on each set of cylinders. In a V-6 or V-8 engine, this is typically bank-to-bank. Depending on the design, inline engines may run split twin or dual-inline parallel turbos. A parallel system is also the most common aftermarket system, as it’s the easiest to design, install, and tune.

Shop now for universal turbochargers and turbo kitsSequential Turbo

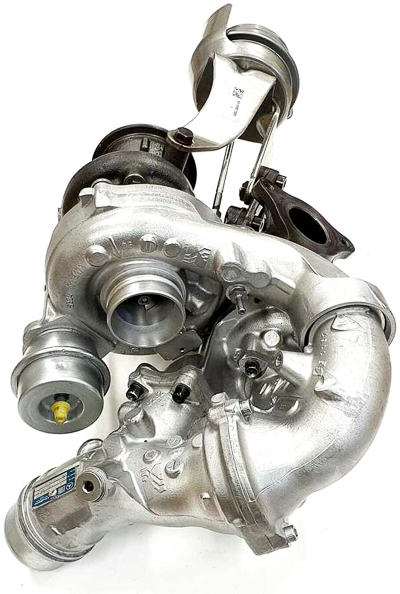

A sequential twin turbocharger for a Mercedes Benz C220

By using a smaller “fast spool” turbo for low rpm and a second larger turbo for high rpm, a sequential system can spool up nearly instantly and then maintain boost across the entire rpm range.

Multiple designs exist, but most sequential turbos use a gated system where only the smaller unit engages at lower rpm. As the engine revs higher, the gate opens, allowing the exhaust to spool the larger turbo. This generates a smooth boost transition, so you don’t feel the second turbo kicking in; you just get a lot of power. The complicated designs of these systems make production complex, and they are rarely used today.

Series or Two-Stage Variable Turbocharging

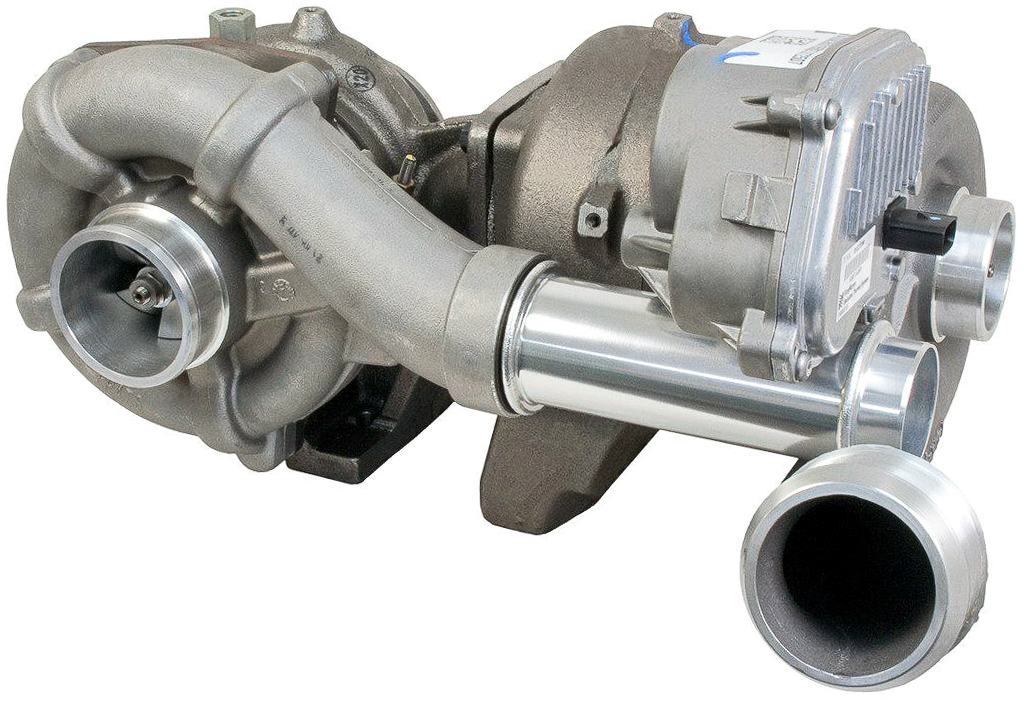

Series systems use one turbo to boost the initial air intake charge, which is further compressed by a second turbo. This reduces overall lag compared to running a single large turbo, but it’s less efficient than other systems. Series or two-stage twin-turbos generate much larger boost levels at lower rpm than a single turbo can, making them perfect for diesels and static-rpm engines like boats and airplanes.

A series twin-turbocharger assembly for a Ford 6.4L Powerstroke diesel V-8

Twin-Scroll Turbo

A T70 type twin scroll turbocharger

Not really a twin-turbo, the twin-scroll uses two separately chambered exhaust paths to drive the same impeller within a single turbo housing.

Most commonly used on small four- and six-cylinder engines, the twin-scroll separates the exhaust in half, with each chamber fed by a set of cylinders. This maximizes exhaust efficiency and allows the engine designer to use wider overlap camshaft profiles while maintaining the maximum pressure. This is the most efficient turbo design for smaller engines, and it’s been used by Saab, GM, Mitsubishi, and BMW for their smallest turbo engines.

Cross-Bank Turbocharging

BMW developed this version of the twin-scroll turbo for a V-design engine. Instead of using two standard turbos, two twin-scroll turbos feed half of each bank of the V.

Wildly complicated, incredibly efficient, and tuned within an inch of its life, the BMW cross-bank system is unique in more than just the turbo design: the engine operates backwards. The exhaust comes in through the interior of the V, where the intake usually is, and the intakes are on the outside of the V, where the exhaust manifolds typically are.

Shop now for BMW car & truck turbochargers

A pair of aftermarket turbochargers for a BMW N53 cross-bank V-8 engine

Twin-turbos are more than just bragging rights for gearheads. A Kia Stinger GT2 parallel twin-turbo 3.3l V-6 makes 368 horsepower, while a GM 5.3l Gen V LT-series V-8 makes 350. Twins win pretty much every time.